Putting China’s Shrinking Population in Perspective

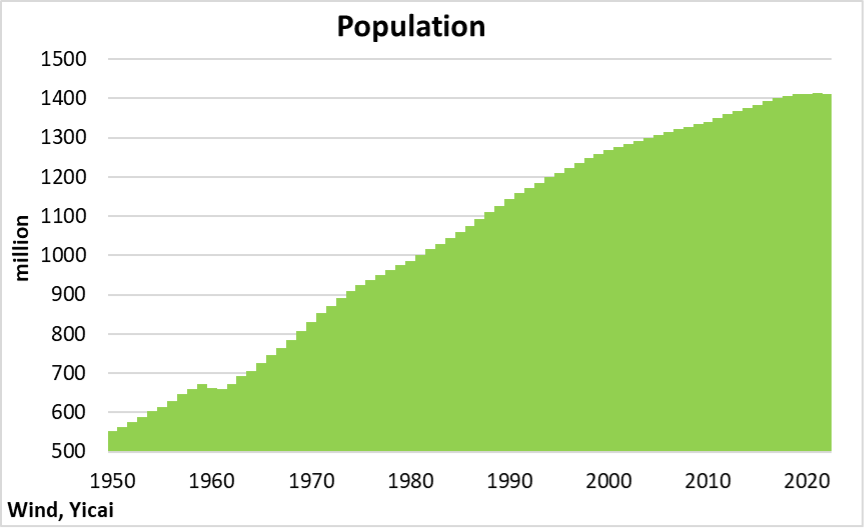

Putting China’s Shrinking Population in Perspective(Yicai Global) Feb. 6 -- The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) recently announced that China’s population shrank by 850,000 in 2022. This 0.1 percent decline follows zero growth in 2020-21 and suggests that the number of people in China has peaked (Figure 1).

Last year was the first time that China’s population fell since the early 1960s when a major famine led to a spike in the number of deaths and the population falling by 13.5 million (2 percent) between 1959 and 1961.

Figure 1

Demographers had been expecting China’s population to peak in the early 2030s. So, if current trends continue, China will be facing demographic pressures much earlier than anticipated. The NBS’s announcement has caused considerable handwringing in the press and calls for government action to support population growth.

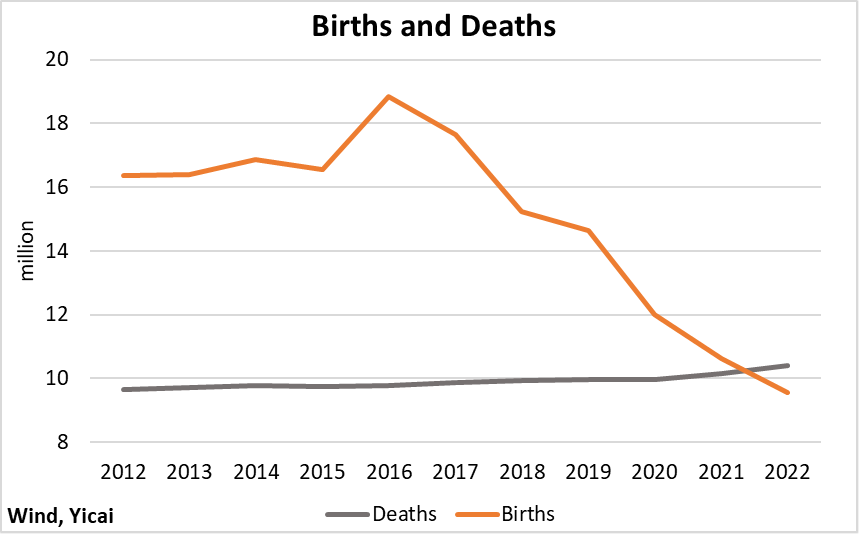

Last year, the population dipped because there were 10.4 million deaths and only 9.6 million births. The number of births had been falling steadily from a recent peak of 18.8 million in 2016, while deaths ticked up slightly (Figure 2).

Figure 2

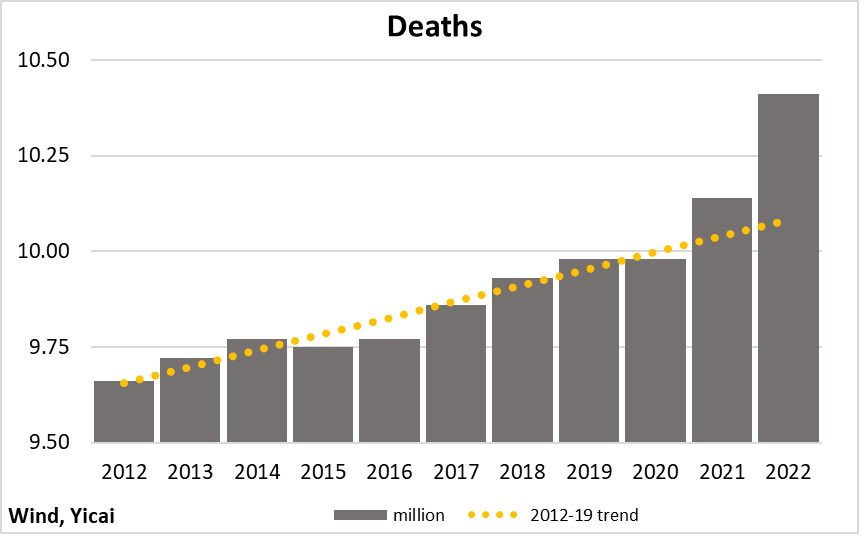

Life expectancy at birth continues to rise in China. In 2020 it was 78 years, three years higher than in 2010 and nine years higher than in 1990. Nevertheless, the annual number of deaths has been trending up over the last decade, likely because the population is aging. Deaths in 2022 were some 328,000 higher than a simple linear trend would predict.

Figure 3

According to Wang Pingping the Director of the NBS’s Population and Employment Department, the decline in China's population was mainly due to the decrease in the number of births.

Wang gives two reasons for the falling birth rate. First, there were fewer women of childbearing age. The number of women aged 21-35 fell by nearly five million last year. Second, fertility – the number of children each woman has – is also declining. Wang says that fertility is affected by a variety of factors including marrying later and changing attitudes toward childbearing.

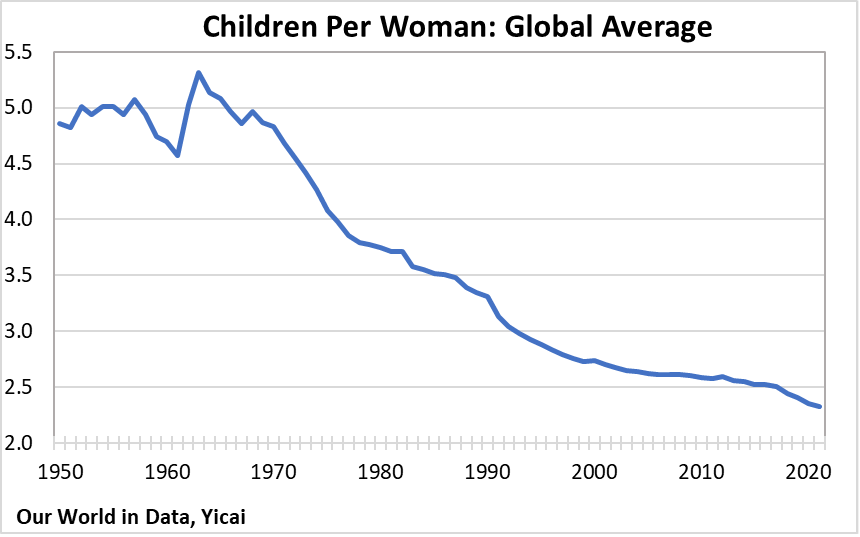

Chinese women are not the only ones who are opting for fewer children: declining fertility is a global trend (Figure 4). As recently as 1990, women around the world had 3.3 children, on average. By 2021, they were only having 2.3. Demographers say women need to give birth to 2.1 children, on average, to maintain the population at its current level.

Figure 4

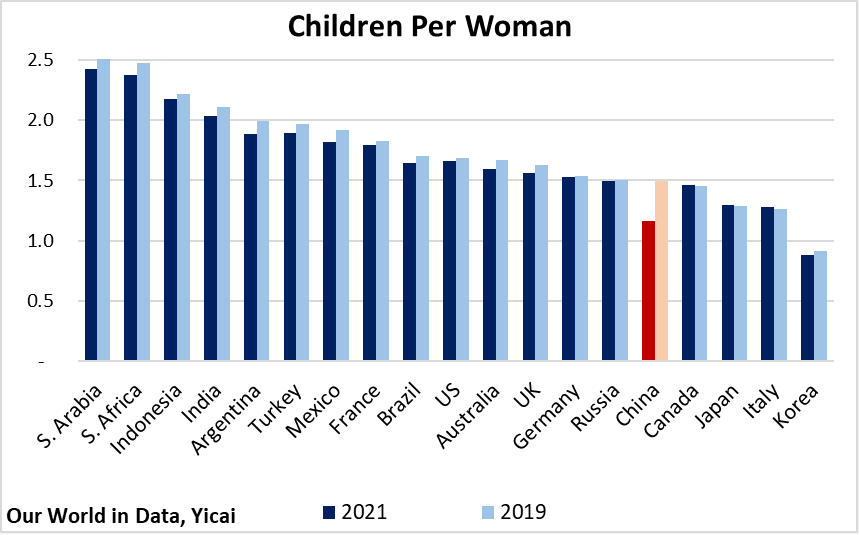

Looking across the G20 countries, China’s fertility rate is low, but it is not an outlier. In 2021, China had the second lowest fertility rate in the group. Only Korea’s was lower (Figure 5).

In most of the G20 countries, fertility dropped from the levels recorded in 2019, likely because of the dislocation caused by Covid. The decline was especially sharp In China. In 2019, before the pandemic hit, China’s fertility rate was the 5th lowest – just behind Russia’s and slightly ahead of Canada’s.

China’s pandemic-related decline in fertility is understandable. During the past three years, my friends have tried to avoid going to hospitals, which they saw as hotbeds of infection. This is, perhaps, why more women decided to postpone having children.

Given the decline in births noted above, China’s fertility rate almost certainly fell further in 2022. The key question is whether the passing of the recent Omicron wave and the normalization of public health policies implemented last December will unleash a pent-up demand for children in the coming years.

Figure 5

While there are pandemic-related reasons for the decline in births between 2019 and 2022, longer-term factors are also at work keeping fertility in China low.

In many societies, women do most of the child-rearing. Women’s willingness to bear children will depend, in part, on what opportunities they have outside of the home. The value of these opportunities will be closely related to how well educated women are.

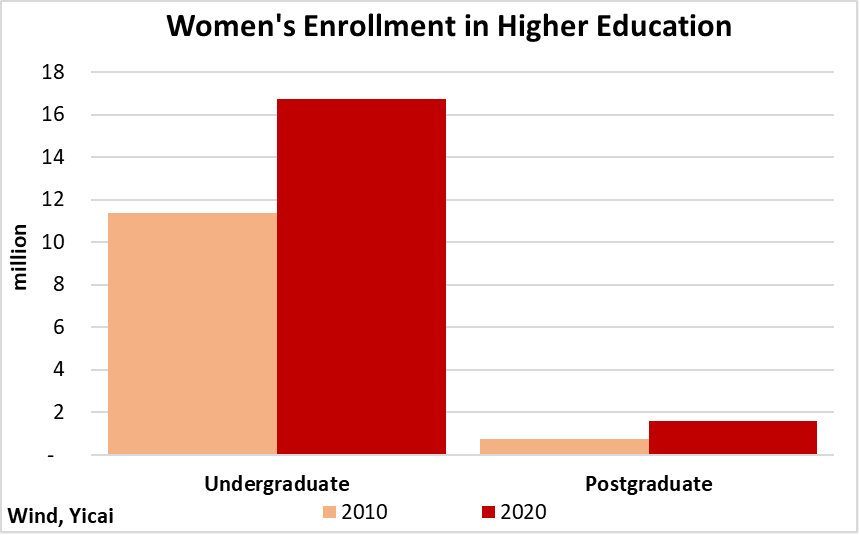

Over the last decade, more and more Chinese women have benefitted from higher education. Women’s enrollment in undergraduate studies rose by 47 percent between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 6). Women make up 49 percent of China’s population but in 2020, they comprised 54 percent of the students in regular undergraduate programs. This was up from 50 percent in 2010.

Similarly, women’s enrollment in postgraduate programs more than doubled between 2010 and 2020. Women comprised 53 percent of the students at the master’s level in 2020 (up from 50 percent in 2010) and 42 percent of those at the doctorate level (up from 35 percent).

Given this increased access to education, it is no surprise that more women decide to postpone having children, have fewer children or decide against having children altogether.

Figure 6

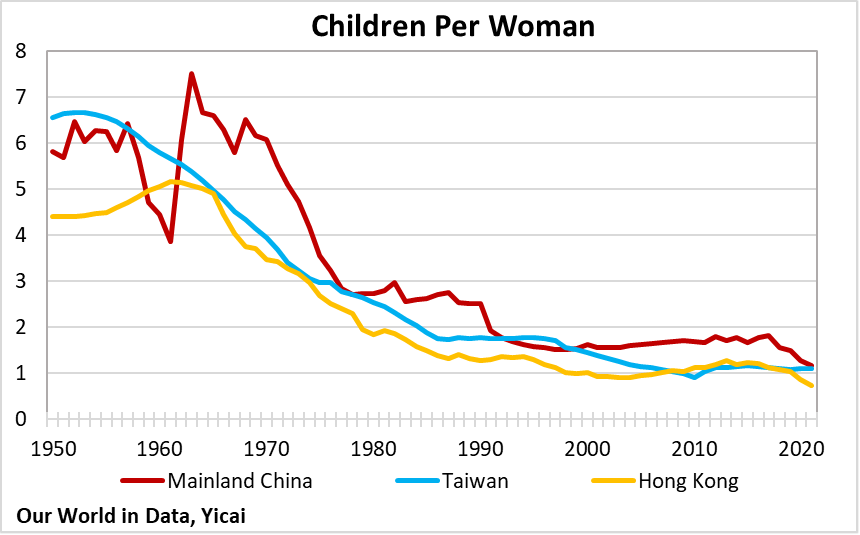

Many commentators attribute the Mainland’s low fertility rate to the one-child policy. However, fertility had already more than halved by the time the policy was phased in between 1978 and 1980. Moreover, the trajectory of fertility in the Mainland has been very similar to those in both Taiwan and Hong Kong, where the one-child policy was not implemented. Fertility fell to one child per woman in Hong Kong about 20 years ago and in Taiwan ten years later. The Mainland is approaching that level now (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Women in China are not alone in preferring smaller families. As shown in Figure 5 above, women in Korea and Japan also tend to have fewer children than those in other G20 countries.

Research by Cai and Morgan suggests that cultural factors could be at work. They look at the childbearing behaviour of Chinese, Japanese and Korean women living in the US. Compared to “white” American women, these Asian women tended to postpone childbearing and have fewer children over their lifetimes.

Their preference for fewer children is not due to their better education. At all levels of educational attainment, the Asian women had lower fertility rates than those of their “white” counterparts. Moreover, Asian women’s preference for small families runs deep. Women of Chinese, Japanese and Korean ethnicity born in the US had fertility rates that mirrored those in their countries of origin.

So, what should policymakers do about China’s shrinking population?

Some commentators believe that the policy objective should be to make the Chinese economy as big as possible. They believe that power comes with size. So, they suggest offering subsidies to families to encourage them to have more children.

On the other hand, policymakers may want to focus on raising living standards. In that case, maximizing GDP per person rather than GDP itself would be the objective and resources should be targeted to raise productivity by investing in physical and human capital and optimizing the use of existing human resources.

I have previously suggested three ways that policy can be used to offset demographic decline. I will not go into the details again here but let me offer a summary.

First, policymakers can increase the retirement age. In China, female workers currently retire at 55 and males at 60. These low retirement ages are an artifact of earlier years when the priority was to ensure the employment of young people. Raising the retirement age by five years would increase the pool of potential workers by some 8 percent.

Second, policymakers could facilitate the exit of workers from low-productivity activities like agriculture and encourage further urbanization. According to Wang Pingping, China’s urbanization rate reached 65 percent in 2022, up one-half a percentage point from the previous year. In developed economies, about 80 percent of the population lives in cities, where productivity and wages are higher. Further urbanization would entail far-reaching reform of the hukou system.

Third, policymakers could make additional improvements in workers’ human capital. Wang Pingping noted that the working-age population’s average number of years of education continued to rise and reached 10.9 in 2022. This is good news. Increasing educational attainment will boost productivity and has the potential to fully offset demographic decline.

To sum up, last year’s dip in the population was, to some extent, the result of the pandemic and could be temporary. Nevertheless, unless China’s birth rate rises to 2.1 children per woman, its population will decline. Improvements in women’s education and the increase in the opportunity cost of having children are depressing China’s fertility rate. Cultural factors also play a role. Luckily, there are steps policymakers can take to mitigate the effect of a smaller population on living standards.