Is China Facing a Demographic Crisis?

Is China Facing a Demographic Crisis?(Yicai Global) June 1 -- On May 11, the National Bureau of Statistics released the results of its seventh National Census. These once-a-decade enumerations of China’s population provide the most comprehensive picture of the nation’s demographics. Media reports focused on the slow growth in the overall number of people and the aging of Chinese society. They warned that China faced a “demographic crisis”.

Indeed, from a macroeconomic perspective, the news was not good.

The key data point was the decline in the population aged 15-59, from 940 to 894 million since the previous census in 2010. This is China’s “working-age” population. The five percent drop in the pool of potential workers – 0.5 percent per year – represents the loss of a key input for building GDP.

Looking ahead, the news only gets worse.

The decline in China’s working age population is expected to accelerate over the coming decades. Projections from the United Nations suggest that between 2020 and 2050, the amount of 15-59 year-olds will fall by 23 percent, or 0.9 percent per year.

What does this mean for GDP growth?

According to standard models, a 1 percentage point decline in employment translates into a fall in GDP growth of 0.55 percentage points. If a constant share of the working-age population is employed, then the projected decline in the 15-59 year-old group would shave 0.5 percentage points off of annual GDP growth over the next 30 years.

China will likely grow between 4-5 percent per year over the next 15 years and perhaps between 2-3 percent per year over the following 15 years. So, losing ½ a percentage point in growth due to unfavourable demographics should not prevent Chinese people from increasing their standard of living.

However, with workers comprising a falling share of the population, their earnings will have to be spread more widely in order to support an increasing number of dependents.

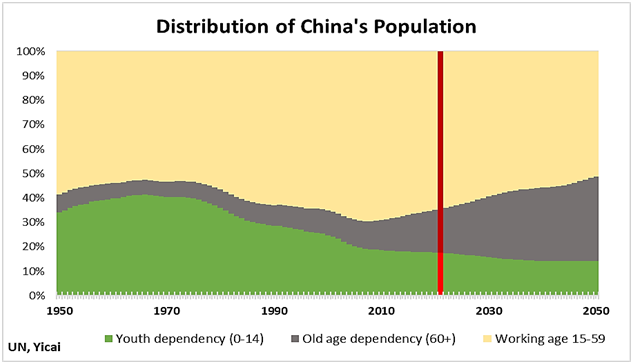

Figure 1 shows the outlook for China’s dependency rates to 2050, based on projections by the United Nations. China reached its demographic peak in 2008. At that time, the working-aged comprised close to 70 percent of the population, with the young and the old together accounting for the remaining 30 percent. The share of those 60 and over is expected to rise rapidly and reach 35 percent by 2050. Those under 15 will fall to 14 percent and the working-aged will account for 51 percent of the total population.

Figure 1

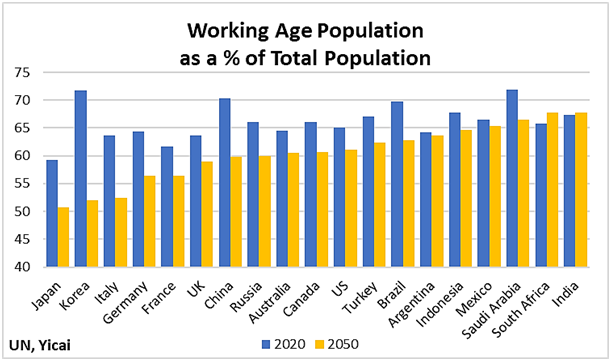

China is not alone in facing this sort of demographic challenge, although its transition over the next three decades is predicted to be among the most extreme. Figure 2 shows the working-age population (here we use 15-64) as a share of the total population for the G20 countries in 2020 and in 2050.

Figure 2

In 2020, the Chinese economy benefited from a relatively high share of working-age people. It ranked third after Saudi Arabia and Korea. However, by 2050 China’s ranking will fall to seventh lowest. Only Korea and Italy are expected to experience more precipitous increases in dependency.

So, what can be done to manage this demographic decline?

One obvious policy response would be to increase the retirement age. In China, female workers currently retire at 55 and males at 60. These low retirement ages appear to be an artifact of earlier years, when the priority was to ensure the employment of young people. Around the world, governments are worried about the effect of poor demographics on their pension systems and they are trying to find ways to keep people employed longer. There is no reason why China cannot be part of this trend.

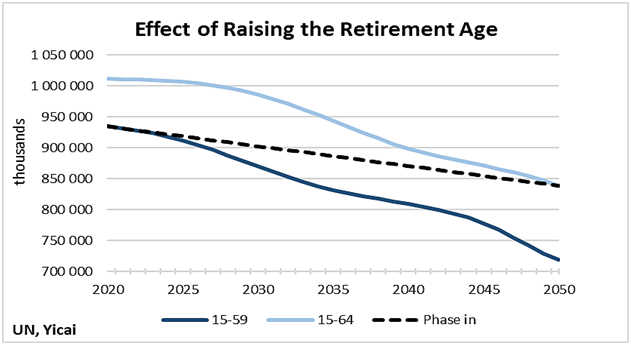

Raising the retirement age by five years would give the Chinese economy access to a pool of close to 80 million additional workers. However, even the 15-64 age group is expected to decline over time (Figure 3).

Suppose China gradually phased in a five-year increase in the working age over the next 30 years, consistent with the dashed line in Figure 3. The resulting decline in the working-age population would only be 10 percent, compared to the 23 percent fall in the 15-59 age group. Thus, raising the retirement age by five years doesn’t eliminate the problem of demographic decline, but it cuts it by more than half.

Figure 3

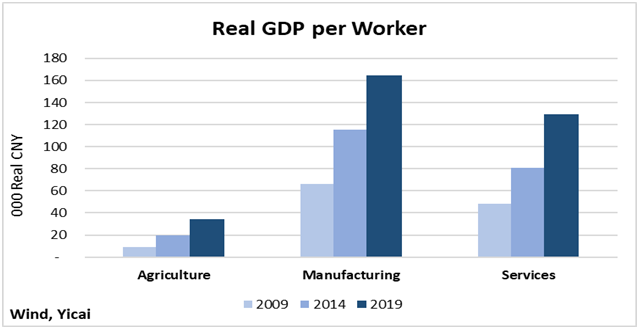

With labour increasingly at a premium, China needs to make the best possible use of its workforce. Yet, the large differences in productivity across the three broad sectors of the economy suggest potentially large gains from reallocating workers.

Figure 4 shows productivity – real GDP per worker – in agriculture, manufacturing and services. Productivity in each of these sectors has increased over time. Still, it remains much lower in agriculture than in manufacturing and services.

Figure 4

Agriculture employs about a quarter of China’s workforce. What kind of productivity increase might we expect if some of these farm workers shifted to more productive undertakings?

Let’s do a thought experiment. Let’s assume that current levels of productivity and the overall size of the labour force are unchanged. Now, let’s reduce the share of workers in agriculture from 25 percent to 10 percent. This is not an extreme assumption. Agriculture’s share of China’s workforce actually fell by 25 percentage points over the last two decades. Moreover, in OECD countries, agriculture only employs 5 percent of the workforce.

We now re-employ these workers in the service industry, where productivity is close to four times as high. In this thought experiment, the reallocation of labour raises GDP by 12 percent. If we would allow this transition to take place over 30 years, the increase in annual growth would be 0.4 percent – enough to offset much of the impact of the decline of the 15-59 year-olds.

In the preceding thought experiment, we left productivity unchanged. However, it is likely that productivity will continue to increase such that a Chinese worker 30 years from now will be capable of supporting more dependents than a worker today.

One of the key channels through which productivity increases is education. According to economic theory, workers become more productive as they accumulate “human capital”, which is modelled as proportional to the number of years of education.

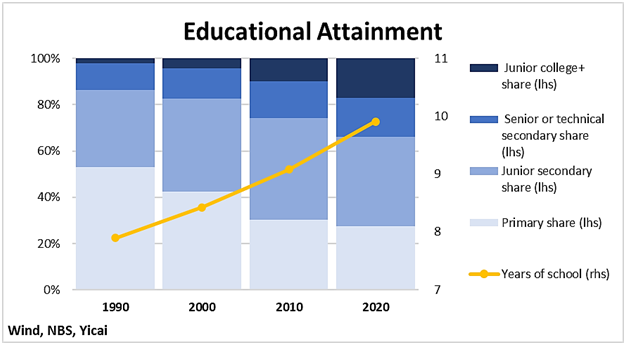

The recent census shows that China’s educational attainment continued to increase. In 2020, those aged 15 and above had, on average, 9.9 years of schooling. That was up from 9.1 years in 2010 (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Over the next 30 years, it is reasonable to expect that educational attainment will increase further. Let’s assume that average years of schooling rises to 12.2 years by 2050. That’s where Korea is today. By comparison, Germany is at 14.2 and Canada, Switzerland and the US are at 13.4.

If human capital increases one-for-one with years of education, that means that after 12.2 years of schooling, the average worker would be 23 percent more productive than one today. Thus, the increase in productivity would fully offset the effect of the decline in the population aged 15-59.

The results of the census have already caused a re-think of China’s population policies. This week, the government relaxed restrictions and allowed families to have three children. However, encouraging couples to have more children is likely to be difficult, especially in cities, given the high costs of living. Moreover, policies to increase the retirement age are liable to be unpopular, as Chinese grandparents provide important non-paid work, which facilitates their children’s participation in the labour force.

However, the good news is that further educating the workforce and reallocating it more efficiently are potentially very effective tools for managing China’s demographic decline.