China’s Balance of Payments Show The Dual Circulation Strategy At Work

China’s Balance of Payments Show The Dual Circulation Strategy At Work(Yicai Global) April 13 -- A strong undercurrent of self-reliance runs through China’s 14th Five Year Plan.

On the supply side, the Plan emphasizes innovation-driven development. It sets ambitious targets for R&D, the creation of patents and the value added of core digital technologies.

Self-reliance also motivates the push to raise the quality, efficiency and competitiveness of China’s agricultural sector. The Plan raised the target for domestic grain production by 18 percent to 650 million tons. The 13th Five Year Plan had only targeted a 10 percent increase, to 550 million tons.

It is easy to see why China is looking to safeguard the supply of key inputs – from chips to wheat – given the backlash against globalization and the loss of respect for the rules-based multilateral trading system.

On the demand side, the 14th Five Year Plan calls for enhancing the “fundamental role” of consumption in China’s economic development.

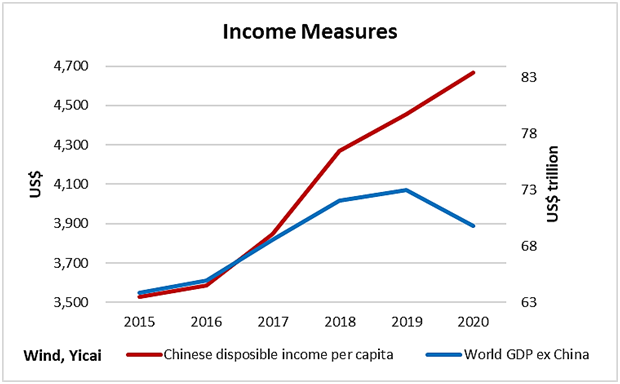

The rationale for relying on domestic demand is also straightforward. Until recently, Chinese consumers have not been rich enough to fuel demand for quality products. But that is changing. Not only have Chinese households become much wealthier, but their income growth is also impressive, compared to what we see elsewhere in the world.

Figure 1 shows that the level of Chinese personal disposable incomes, in US dollars, grew by close to a third between 2015 and 2020. In contrast, global GDP ex-China only grew by 9 percent over the same period.

So, it appears as if a tipping point may have been crossed and China can now increasingly rely on domestic consumption as a source of demand for high-end goods and services.

Figure 1

Does increased self-reliance mean that China is turning its back on the rest of the world?

With China’s productivity still lagging the global leaders’, that would be foolhardy. China needs to learn from the rest of the world in order to keep moving toward the technological frontier.

In return, China can offer the rest of the world a growing market in which it can scale up new products and processes. China’s market is likely to be most attractive to innovators in smaller countries that do not have a strong sales base over which they can spread R&D costs.

It is this bargain that lies at the heart of the “Dual Circulation Strategy”, the development paradigm first proposed by President Xi last May. According to the 14th Five Year Plan, China must strengthen the leading role of domestic circulation, use international circulation to improve domestic circulation’s efficiency and achieve mutual benefit.

As a matter of policy, then, China will continue to deepen its engagement with the rest of the world.

China’s balance of payment accounts provide the most extensive record of its international transactions. The most recent data show that, despite the dislocation caused by the pandemic, China and the rest of the global economy have never been so tightly interlinked.

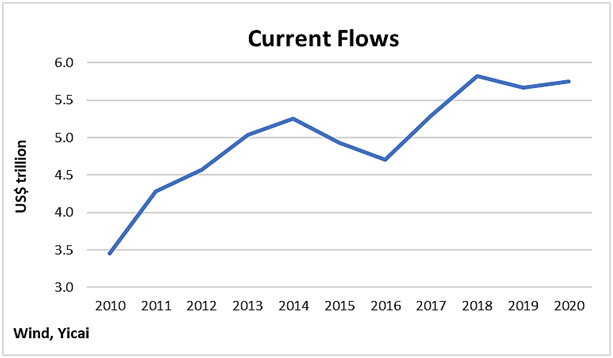

The current account records payments and receipts for goods, services and income earned abroad. International trade in goods and services collapsed last year. Nevertheless, China’s current transactions ticked up to USD5.7 trillion, the second highest amount on record (Figure 2). China’s success, in an otherwise dismal market, was due to its ability to control the spread of the virus and get its supply chains in shape to benefit from a surge in foreign demand for durable goods.

Figure 2

Payments for goods dominate China’s current transactions with the rest of the world, accounting for close to four-fifths of the total last year. Both exports and imports of goods grew modestly, which was no mean feat all things considered.

The pandemic did have a strong impact on China’s service trade. In particular, there was a sharp decline in cross-border travel. With its growing middle class increasingly fond of international tourism, China has imported a significant amount of travel services in recent years. Its payments for travel services in 2019 were close to six times as high as in 2009.

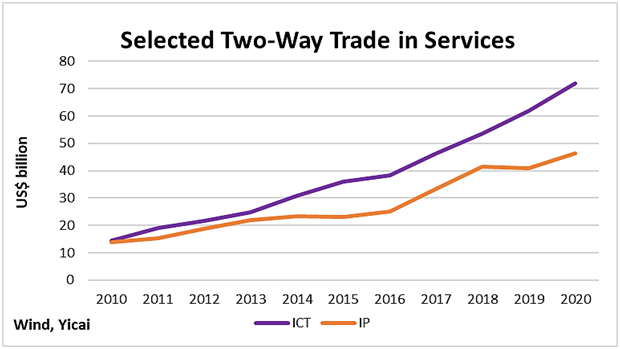

While travel suffered a pandemic-related decline, other elements of the service account reveal China’s growing interconnection with the rest of the world.

Figure 3 shows the tremendous growth of the trade in information and communication technology (ITC) services and for two-way payments for intellectual property (IP). China’s payments for IP essentially tripled between 2010 and 2020, while its IP receipts have grown ten-fold (from a much lower base).

Figure 3

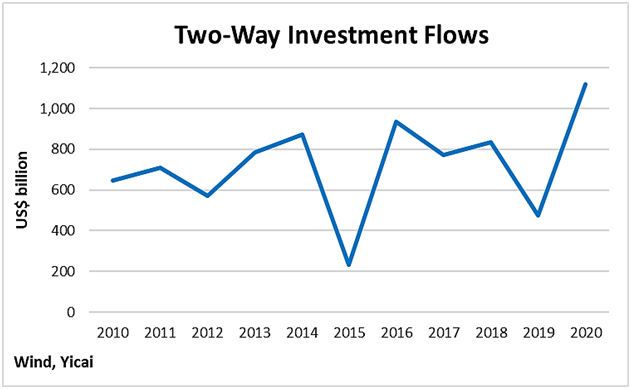

The financial account of China’s balance of payments tracks transactions in assets and liabilities. Figure 4 shows that these two-way investment flows hit a record high in 2020.

Figure 4

Three types of investment flows are recorded in the financial account.

The first is direct investment: the construction of new facilities in a foreign country and cross-border mergers and acquisitions. These are typically long-term investments, which are not easily liquidated.

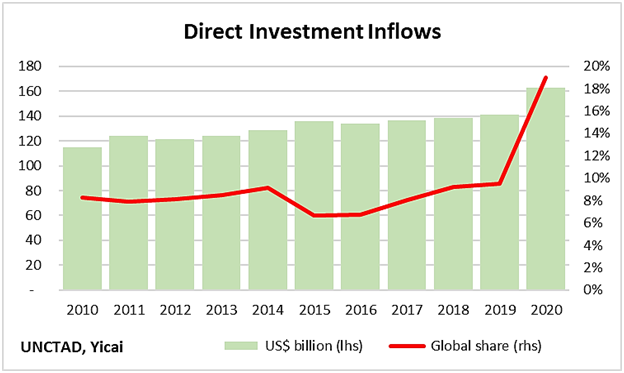

Last year, global foreign direct investment flows dropped by more than 40 percent, falling to their lowest level since 2004.

In this context, both Chinese direct investment abroad and direct investment in China held up very well, with flows in both directions increasing. Indeed, despite the uncertainty caused by the Trump Administration’s trade policy, inflows were surprisingly strong and China surpassed the US to become the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment (Figure 5).

Figure 5

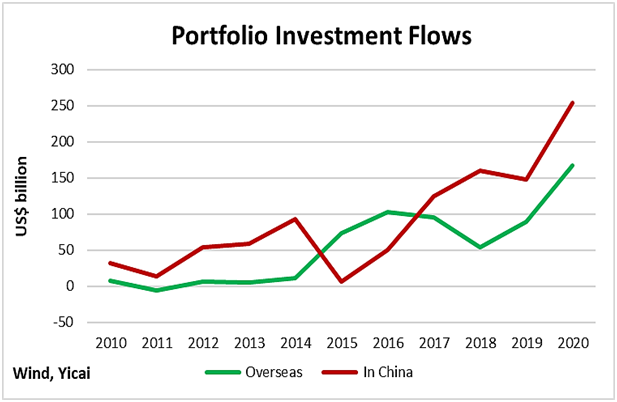

Cross-border investments in financial assets, like stocks and bonds, represent the second type of financial flow. These “portfolio” flows tend to be shorter term than direct investments and are easily liquidated in deep markets.

China’s inward and outward portfolio flows both spiked last year.

Foreigners, attracted by the relatively high yields on Chinese bonds and their inclusion in global indices, made record investments in Chinese debt markets.

Meanwhile, Chinese investors bought more foreign equities in 2020 than in the previous four years combined. Many of these purchases were made in Hong Kong, where initial public offerings were up sharply. Chinese investors were eager to purchase stakes in familiar names such as JD.com, JD Health International and NetEase.

Figure 6

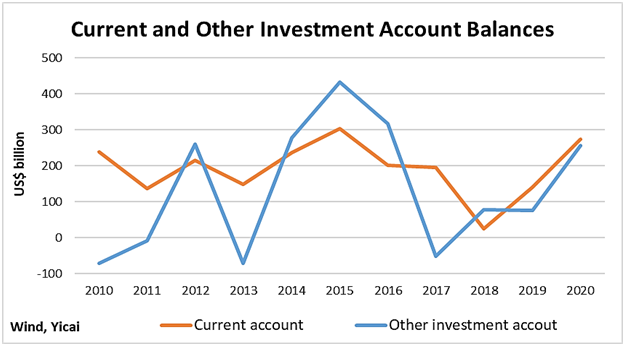

The remaining items on the financial account are called “other” investment flows. They essentially reflect changes in bank-related assets and liabilities (cross-border loans and deposits).

Chinese lenders were very active last year. Their international loans rose by a record amount. Moreover, Chinese residents also increased their deposits abroad by the most since 2014.

Unlike the elements of the balance of payments discussed above, which are seen as desired or “autonomous”, other investment flows are seen as financing items and are characterized as “induced”. A country needs to pay for its balance of payments deficit and other flows are a key channel through which this financing happens.

Figure 7 shows that the other investment account tracks the broad movements in the current account. China’s current account surplus rose last year. The increase in loans by Chinese banks and deposits by Chinese residents helped provide foreigners the funds required to purchase Chinese goods and services.

Figure 7

In sum, the picture painted by the balance of payments accounts is one of China ever more intimately engaged with the rest of the world. The resilience of China’s goods and services trade, the robustness of direct investment inflows and the sharp growth in two-way portfolio flows are evidence of the Dual Circulation Strategy at work.