How Long Will Foreign Investors’ Love Affair With Chinese Bonds Last?

How Long Will Foreign Investors’ Love Affair With Chinese Bonds Last?(Yicai Global) Dec. 10 -- Foreign inflows into the Chinese onshore bond market continued to grow rapidly in November. Foreigners now hold more than CNY3 trillion (USD460 billion) in Chinese bonds, triple the amount they held only three years ago.

While macroeconomic and institutional factors account for foreign investors’ recent infatuation with Chinese bonds, the benefits of portfolio diversification and the creation of an international financial center in Shanghai will underpin a steady long-term relationship.

Despite foreign investors strong interest in Chinese bonds, their holdings comprise less than 3 percent of the entire onshore bond market. Nevertheless, since foreign investors are focused on buying the bonds sold by the highest quality issuers, they are becoming key players in specific markets.

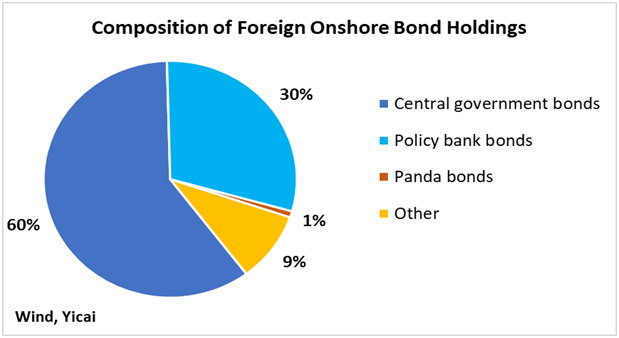

Figure 1 shows that 90 percent of foreign holdings are in bonds issued by the Government of China or one of the three policy banks, which are essentially seen as sovereign risk. Corporate bonds and those issued by local governments only account for 9 percent of foreigners’ holdings, while investment in the small Panda market accounts for 1 percent.

Figure 1

Three factors explain foreigners’ preferences for high-quality bonds.

First, many of the foreign investors in the Chinese market are public institutions – central banks and international financial institutions – whose mandates are limited to holding sovereign or quasi-sovereign debt.

Second, the international indices into which Chinese bonds are being included generally only consider government debt. This leads asset managers who follow these indices to buy sovereign or quasi-sovereign issues.

Third, tax uncertainty related to investment in Chinese corporate bonds has largely kept foreigners away from this asset class.

Given their focused preferences, foreign investors now hold close to 10 percent of the bonds issued by the Government of China and 5 percent of those issued by the three policy banks. They also hold about a sixth of the bonds issued in the Panda market, which is designed to allow foreigners the opportunity of raising onshore RMB funding for their China operations.

In the current macroeconomic environment, Chinese bonds are benefitting from foreign investors’ search for yield. Central banks outside of China are running very accommodative monetary policy to limit the economic fallout from Covid-19. This has led to a precipitous decline in North American and European bond yields.

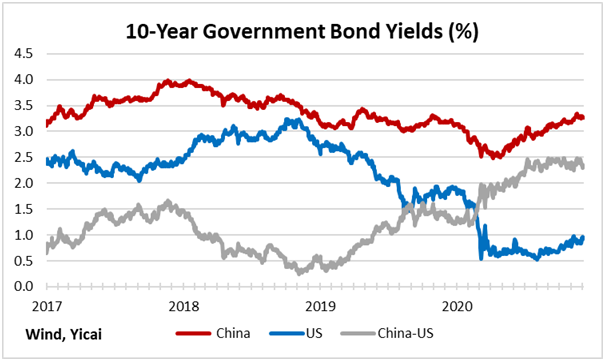

Figure 2 shows that the yield on US 10-year bonds dropped sharply at the beginning of the year and has remained low since. In contrast, that of Chinese 10-year bonds dipped temporarily but returned to its late-2019 level. As a result, the 10-year yield differential has widened to just under 2.5 percentage points, compared to a 1 percentage point differential, on average, over 2017-2019.

Figure 2

High interest rates, by themselves, are not a sufficient inducement to buy Chinese bonds. Investors make their decisions based on their assessments of both reward and risk. Given the risks of investing in Chinese government bonds, these securities appear to be very attractively priced.

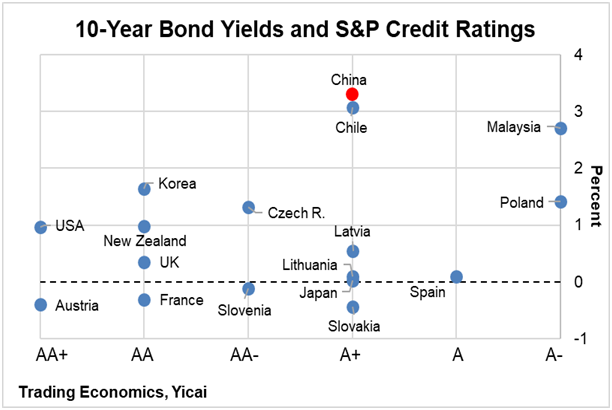

S&P gives China’s sovereign bonds an A+ credit rating. Figure 3 compares the yields on Chinese bonds to those of other sovereigns with broadly similar credit ratings. Not only are Chinese bonds the highest yielding of those rated A+, their yield also exceeds those rated A and A-.

Some of the recent foreign appetite for Chinese bonds can be explained by their being good value for money. Moreover, the reforms undertaken in recent years have improved foreign investors’ access to the onshore bond market. In addition, China’s ability to control the virus and support what appears to be a full recovery suggest that the renminbi is unlikely to depreciate in the near future.

Figure 3

Foreign investment in Chinese bonds is also being supported by their inclusion in major global bond indices. Trillions of dollars track these indices and many investment managers need to purchase Chinese bonds in order to align their portfolios with the benchmarks.

JPMorgan chose to add Chinese bonds to their Emerging Market Government Bond Index in February. Along with those of Brazil, they will be the most heavily weighted, with each country accounting for 10 percent of the benchmark.

More importantly, Bloomberg/Barclays and FTSE/Russell are adding Chinese bonds to their global indices. The former began in April 2019 and the latter will begin in October 2021. The weight of Chinese bonds in these indices will only be between 5-6 percent. But there is a lot more money tracking global bonds than emerging market debt. So, the impact on the Chinese market will be greater.

The three indices are only gradually increasing China’s share towards its target weight. Ultimately, including Chinese bonds in these three indices could mean that foreign investors will need to purchase some USD300 billion in Chinese debt. So, asset managers’ positioning could also explain some of the interest we have been seeing.

Looking beyond the shorter-term macroeconomic and institutional factors, it is reasonable to believe that foreign investors will increase their holdings of Chinese bonds over time.

Chinese policy makers have long sought to enhance the role of capital markets. Increased foreign participation could raise the sophistication of the bond market and create more high-value added jobs in China’s financial sector. This is consistent with the government’s objective of boosting the share of services in GDP as well as transforming Shanghai into an international financial center.

For foreign investors, the Chinese bond market offers not only high returns at low risk, but also the benefit of diversification. Chinese bonds have low correlations with financial assets in overseas markets. This is due to the tendency of Chinese commercial banks to hold their bonds to maturity and China's monetary policy being independent from those of the US and Europe.

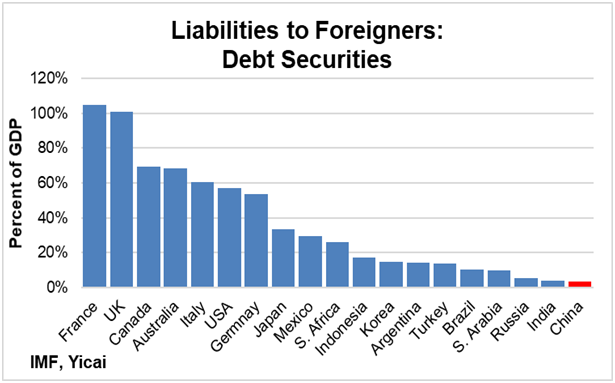

It is important to note that, in some sense, the world is under-invested in Chinese debt. Figure 4 presents the IMF’s data on foreign holdings of debt securities. This measure would include debt held offshore as well as onshore. The data show that at 3 percent of GDP, foreign holdings of Chinese bonds is the smallest of all G20 countries.

Figure 4

So, how long might foreigners’ love affair with Chinese bonds last?

Let’s assume that foreigners’ holdings of Chinese bonds reach the median of the G20 countries, which is 26 percent of GDP. This is where South Africa is in Figure 4. That would imply additional foreign investment of USD3.3 trillion – seven times what foreigners hold today!

Given the benefits to both sides from further capital market integration, it does, indeed, sound like a match made in heaven.