Can a Better-Quality Workforce Mitigate China’s Demographic Decline?

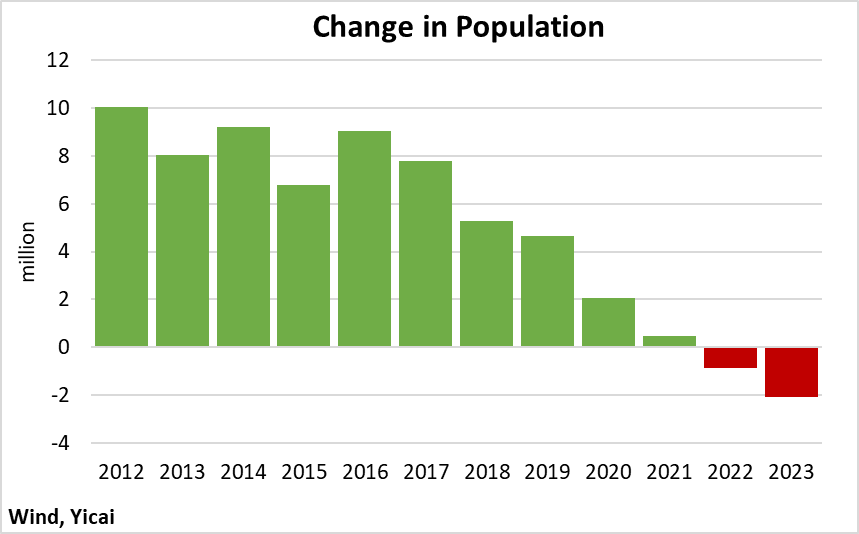

Can a Better-Quality Workforce Mitigate China’s Demographic Decline?(Yicai) Jan. 29 -- With the release of the 2023 National Accounts, the National Bureau of Statistics reported the latest demographic data. The news was not good. China’s population dropped for a second consecutive year, shrinking by just over two million people in 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

China’s unfavourable demographics pose two macroeconomic risks. The first is that GDP could stagnate as fewer workers produce less goods and services. The second is that an aging population creates a higher rate of dependency. In a perfect demographic storm, not only does the economic pie shrink, each worker has to make do with an even smaller slice as there are relatively many non-productive people to feed.

I think that China is very far from such a doomsday scenario. In fact, the recently published 2023 edition of the China Human Capital Report demonstrates how improvements in labour force quality can more than offset the contractionary effects of demographic decline.

The report was published by the Center for Human Capital and Labour Market Research (CHCLMR) at Beijing’s Central University of Finance and Economics. The CHCLMR has been carefully tracking the quality of China’s labour force since 2009 and has published fourteen consecutive issues of the China Human Capital Report.

The OECD defines human capital as “the knowledge, skills, competencies and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being.” Because it resides in people’s minds, human capital is more difficult to measure than physical capital – the value of machinery and structures. The CHCLMR relies on the Jorgenson-Fraumeni method to estimate China’s human capital stock. This approach treats individuals as if they were productive assets and calculates the discounted present value of their expected future incomes. A key component of this calculation is the Mincer equation which relates individuals’ earnings to their education and their work experience. The CHCLMR estimates Mincer equations across genders and regions based on extensive census and survey data.

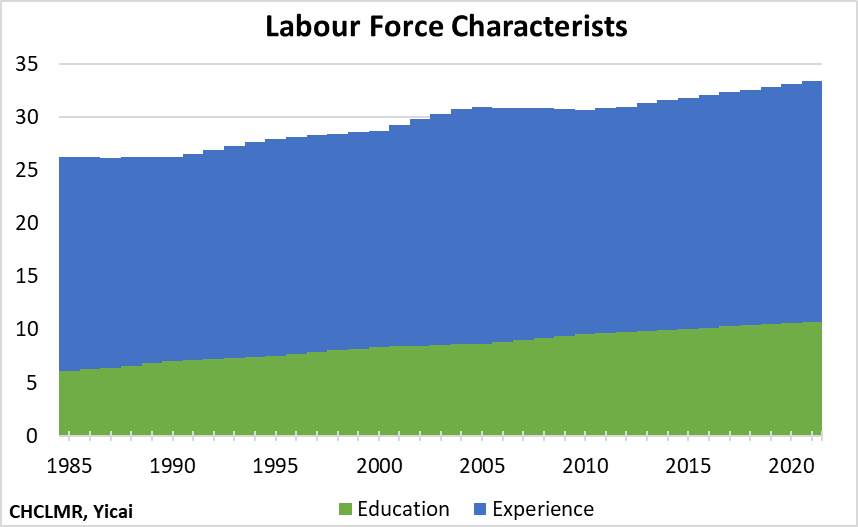

The CHCLMR finds that China’s labour force has become better educated and more experienced over time. Their data suggest that between 2011 and 2021, on average, workers spent an additional year at school and 1½ more years on the job (Figure 2). More education and on-the-job training made workers more productive, with the returns to an additional year of schooling and work experience given by the parameters of the Mincer equation.

Figure 2

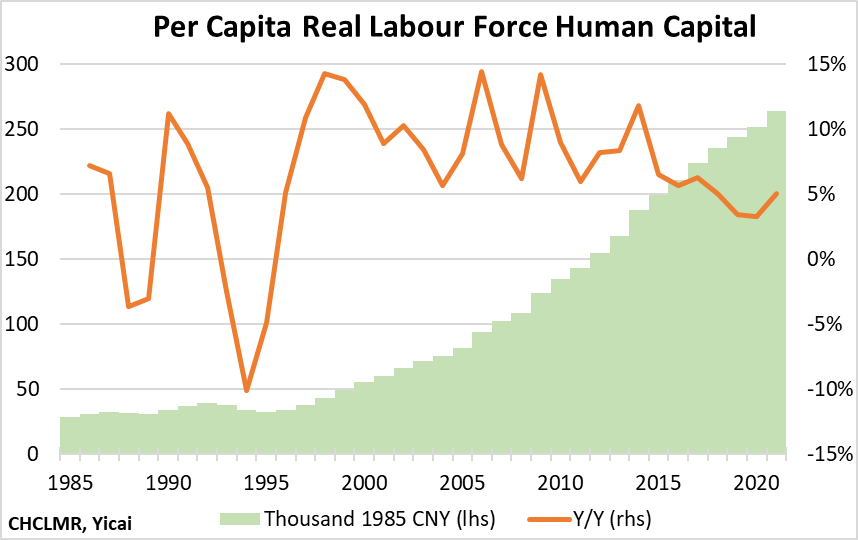

Figure 3 depicts the average worker’s human capital in thousands of 1985 CNY. Between 2011 and 2021, average real human capital rose by 85 percent, or 6.3 percent per year. Its growth slowed in 2019-20 but picked up to just over 5 percent in 2021.

Figure 3

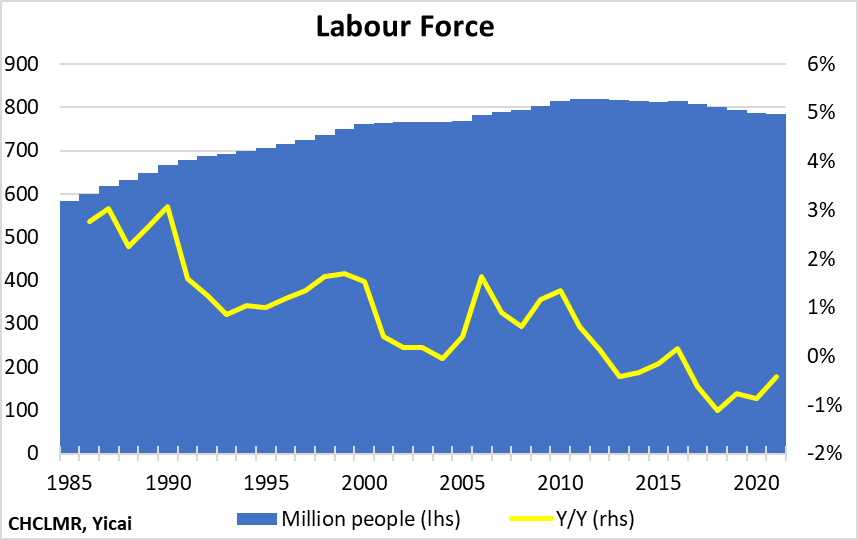

The growth of real human capital per worker was close to 20 times as large as the decline in the labour force (Figure 4). Between 2011 and 2021, the labour force shrank by 4 percent or 0.4 percent per year.

Figure 4

Standard models of the economy’s production side treat the number of workers and human capital per worker similarly. Recent estimates suggest that GDP rises by 0.55 percentage points as a result of a one percentage point increase in either sort of labour input.

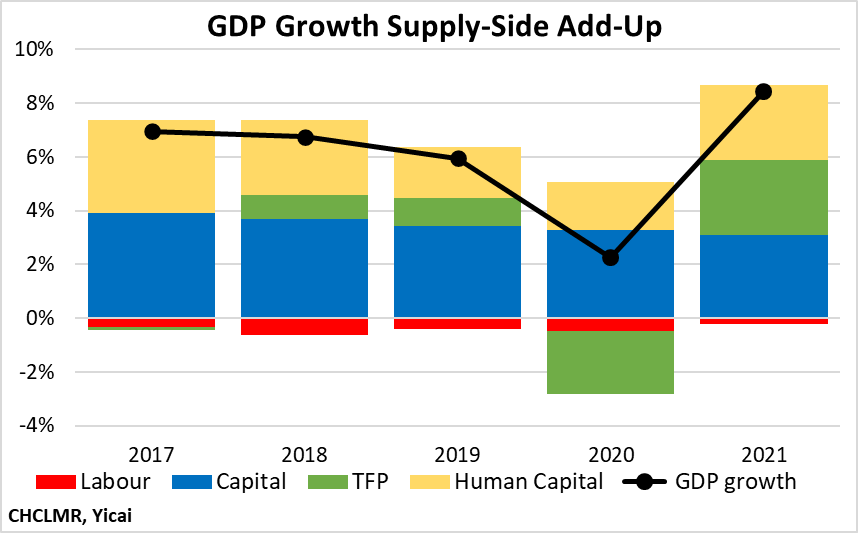

Human capital has been a particularly important driver of growth in recent years. We can see this by embedding the CHCLMR’s estimates for the growth of China’s labour force and its average human capital in a production function. In this production function, the capital input is estimated as the growth of the productive capital stock (which excludes investment in residential real estate).

On average, over 2017-21, GDP grew by 6.1 percent (Figure 5). Human capital accounted for 2.5 percentage points while the decline in the volume of labour subtracted 0.4 percentage points. The growth of the capital stock contributed 3.5 percentage points while total factor productivity (TFP) only added 0.5 percentage points to GDP growth.

Figure 5

In recent years then, improvements in the quality of the labour force have added much more to GDP growth than the decline in the number of workers has subtracted. Looking ahead, the United Nations expects that the decline of China’s working-age population will accelerate to more than 2 percent per year by 2050. Will human capital continue to grow rapidly enough to provide an offset?

I am not in a position to forecast human capital based on CHCLMR’s data, but there are some trends worth noting.

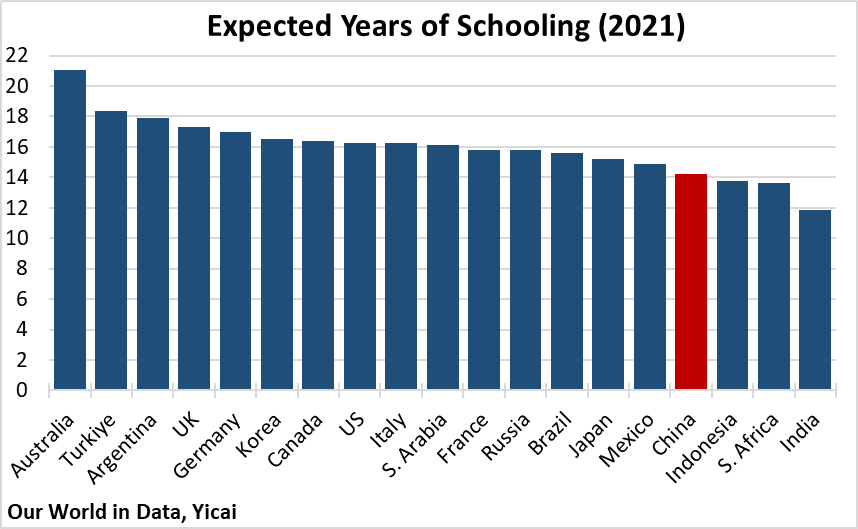

First, cross-country data indicate that there should be considerable scope to further raise educational attainment in China. Figure 6 shows the expected years of schooling across the G20 countries. This represents the amount of years of education a child who is just starting school can expect to receive. At 14.2 years, China ranks 16th among the 19 G20 countries. If China’s expected education rises to approach the G20 average of 16 years, we can expect the productivity of its labour force will rise significantly.

Figure 6

In addition to raising the average level of workforce education, policy can also focus on closing human capital gaps.

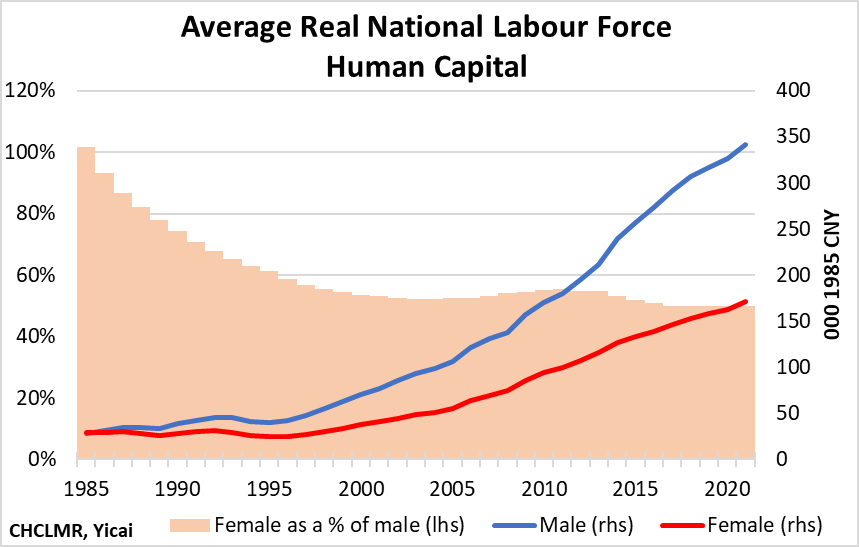

The CHCLMR data show that there is a large difference between the level of human capital of male and female workers (Figure 7). In 2021, average real female human capital was about half that of men. Further study is needed to fully understand the origin of this large gap. With educational attainment between the sexes becoming more equal, I expect that much of the difference is due to women being employed in lower-paying occupations.

Some of the difference could be due to women retiring at 55, five years earlier than men. At 55, women are certainly well-positioned to make important contributions to the economy. Policy could consider increasing the pension payments for women who elect to delay retirement and continue working. Other countries use such incentives to encourage people to work longer.

Figure 7

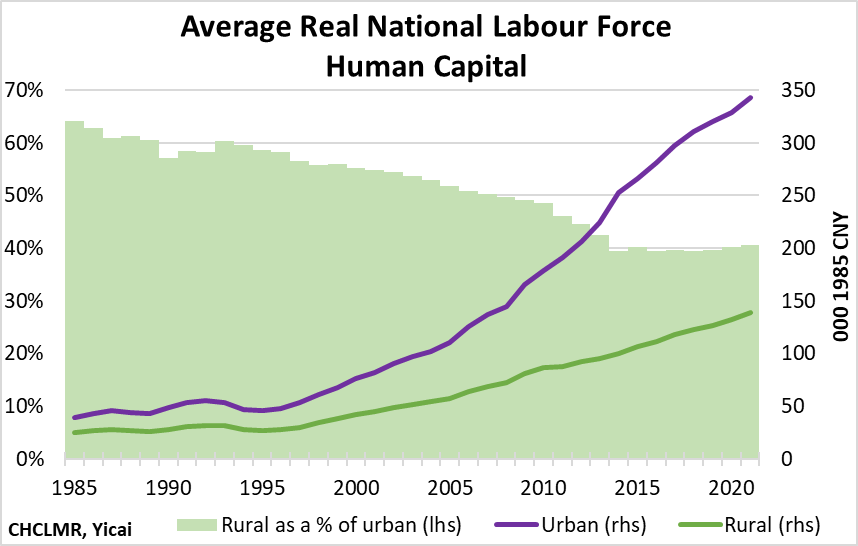

An even larger human capital gap exists between rural and urban workers, on average, with the former having only 40 percent that of the latter (Figure 8). While the returns to an additional year of schooling remains positive for both female and male rural workers, the return to additional years of experience for rural males has turned negative. This suggests that the productivity of rural males is very low and it argues for further reform of the hukou system that will make it easier for families to move to cities where work is better paying.

Figure 8

The CHCLMR’s human capital report provides compelling evidence that improvements in the quality of the workforce have more than offset declines in its quantity. However, the rate of demographic decline is set to accelerate over the next two-and-a-half decades. By highlighting the gaps in urban/rural and male/female human capital, the report also points to ways policy can get the most out of the increasingly valuable Chinese workforce.