China’s Central Economic Work Conference: New Policy Priorities for 2021

China’s Central Economic Work Conference: New Policy Priorities for 2021(Yicai Global) Dec. 26 -- Last week, China’s leading economic policymakers held their annual Central Economic Work Conference. These meetings review developments in the year that is drawing to a close and set priorities for the one about to begin. The statements released at the meeting’s close are indispensable for understanding policymakers’ perspectives and their key priorities.

This year’s document signals the beginning of a new chapter in China’s economic development. The 13th Five Year planning period is ending. The Conference declared that the construction of a moderately well-off society(小康社会)is around the corner and poverty alleviation has been achieved. With citizens’ basic needs cared for, policymakers are turning their attention to building an environment of innovation and technological strength in 2021.

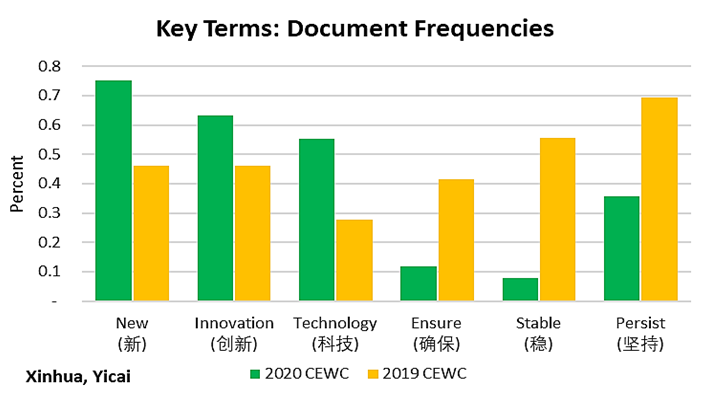

Simple text analytics can be used to illustrate the change in policymakers’ orientation. Figure 1 compares this year’s statement to the one released at the close of 2019’s Conference. It shows that the Chinese equivalents of the terms “new”, “innovation” and “technology” appeared much more frequently in this years’ statement than in 2019’s. In contrast, the terms “persist”, “stable” and “ensure” were relatively more prominent last year.

Figure 1

The Conference’s statement typically enumerates key priorities for the year ahead. This year’s statement had eight.

The first priority is to strengthen China’s strategic technological power. This goal is to be achieved through reliance on a new, whole-of-nation-system (举国体制), a term usually reserved for going all out to build champions in an Olympic sport.

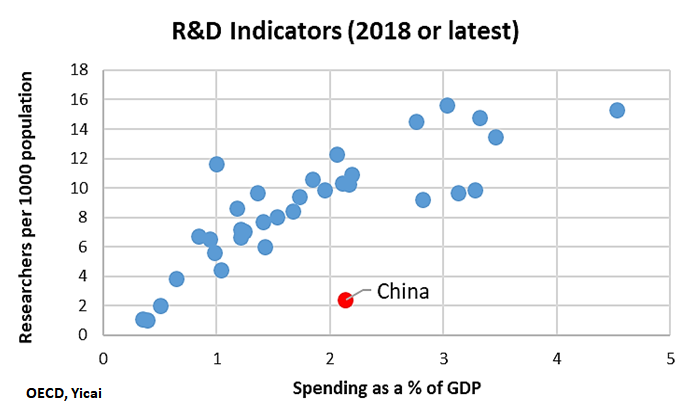

The government is to play a key role in articulating the strategic direction. A ten-year plan is to be formulated for establishing research centers at home, as well as regionally and internationally, as conditions permit. While domestic firms will have the main responsibility for undertaking technological innovation, the benefits of cooperating across country lines are also stressed. This is understandable. While China has been successful at providing resources for R&D, as Figure 2 shows, it has not been able to develop researchers at a pace commensurate with this spending. So, leveraging international partnerships makes sense, as does “accelerating” the training of domestic researchers.

Figure 2

The second priority is to enhance the reliability of the industrial supply chain. Here, policymakers are clearly reacting to trade frictions with the US, which have restricted China’s import of key industrial components. Work is to be focused on resolving “bottleneck problems” and the development of “unique technologies”, which could possibly be used to deter the restriction of key components in the future.

The third priority is to strategically expand domestic demand. While strong domestic demand is needed to keep employment high and incomes growing, consumption, investment and savings need to grow “rationally”. Thus, redundant investment in emerging industries is to be avoided, even as the digital economy is to be “vigorously” developed and “new infrastructure” is to be rolled out across the country.

The fourth priority is to promote “reform and opening up”. Progress is to be made in the three-year plan, approved on June 30, to reform state-owned enterprises. This plan aims to boost the efficiency of state firms and improve their governance, in part, by allowing private firms to purchase ownership stakes. The government will give “active consideration” to joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. Along with joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership this year and ongoing work to finalize the China-EU investment treaty, it shows that China has no intention to turn its back on the rest of the world, despite what people might think about the Dual Circulation theory.

The fifth priority is to ensure food security. The emphasis here is on using science to develop better seeds.

The sixth priority addresses the strong position of Chinese platform companies, such as Alibaba and Tencent. Like its western counterparts, the Chinese government is of two minds about big tech. On the one hand, these companies provide a range of useful services and they push the technological frontier forward. On the other, their dominant market positions provide them with proprietary access to data, which serves to make them even stronger than their competition. The statement notes the need to strengthen the oversight of monopolies and prevent the platform companies from expanding into financial services with a disregard for prudential supervision.

The seventh priority deals with the high cost of housing in big cities. It calls for promoting the construction of affordable rental properties and improving long-term rental policies. Uncertainty over the future stream of their rental payments is one factor that drives families to buy their apartments rather than rent. The economics of renting often compares favorably with those of owning. However, leases are typically only one year long and there is no limit on how high a landlord can raise the rent once it has expired. Finding a way to “conduct reasonable adjustments to rent levels”, would go a long way to addressing a major urban concern.

The eighth priority is to implement China’s commitment to restrain and reduce carbon emissions, which are to peak by 2030 and fall to net zero by 2060. The need to expand carbon sinks by engaging in a “large scale greening of the country” is recognized. It is clear that, even by 2060, China will still be emitting carbon and will need these offsets.

The macro-policy settings appear to be unchanged from 2020. Fiscal policy is to remain “proactive” and monetary policy “prudent”. However, there are some important nuances.

While fiscal expenditures were to be “resolutely reduced” in 2020, they are to be “moderately expanded” in 2021. Moreover, fiscal policy is now tasked with promoting structural change by encouraging innovation, adjusting income distribution and rooting out hidden debts.

Monetary policy is asked to balance the dual objectives of supporting the economic recovery and preventing the emergence of risks. It will keep the money and credit aggregates growing in line with nominal GDP, thereby maintaining a stable macro-leverage (debt-to-GDP) ratio. Last year, the statement asked the central bank to reduce social financing costs. That language was dropped this year, suggesting that we might see tighter monetary conditions.

This year has made it painfully clear that our best-laid plans can go awry in the face of unforeseen events. Notwithstanding all the risks, China’s economy appears to have fully recovered and its policy makers are now focusing on the priorities that will shape national development for years to come.